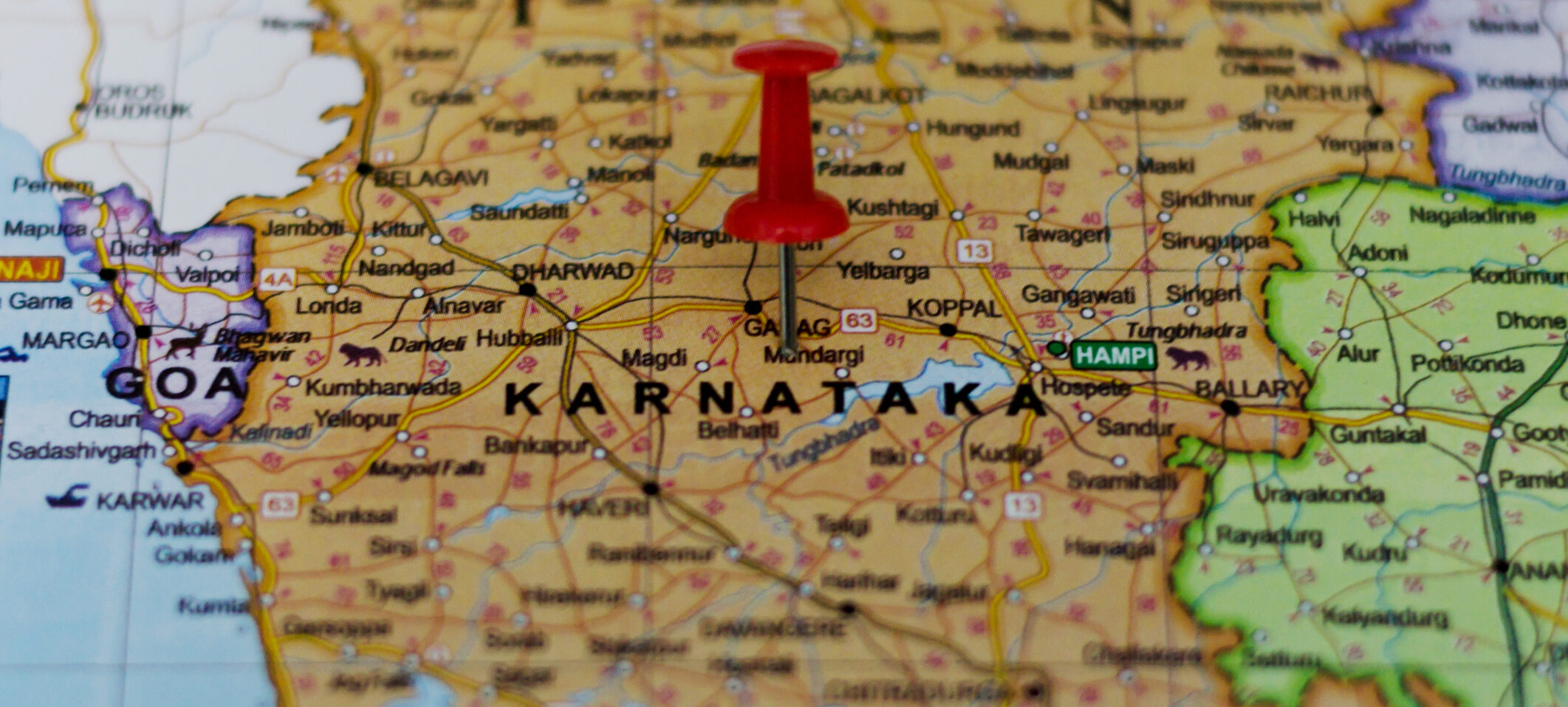

The New GCC Map of Karnataka that Thinks ‘Beyond Bengaluru’

In late October, Bengaluru once again found itself in the national spotlight for reasons that had little to do with technology. A short clip of cratered roads, backed-up traffic and overflowing garbage went viral, accompanied by Biocon chairperson Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw’s exasperated question on X platform: “Why are the roads so bad and why is there so much garbage around? Doesn’t the Govt want to support investment?”

The reaction was immediate and political. Industries Minister M.B. Patil responded that her concerns would be better addressed through CSR initiatives than on social media, while Deputy Chief Minister D.K. Shivakumar defended the city’s ongoing infrastructure upgrades. What began as a public exchange soon took a conciliatory turn, with Shivakumar inviting Mazumdar-Shaw for a meeting that ended in a shared pledge to “find collaborative solutions” to Bengaluru’s civic issues.

It was, at best, a temporary fix for a long-standing problem. The episode reflected Bengaluru’s prevailing mood—a mix of frustration and weary acceptance. Even as traffic crawls, drains overflow and infrastructure strains, residents often fall back on a familiar line: no matter how bad things get, at least the weather is good. The humour, both coping mechanism and commentary, captures how a city once celebrated for its climate of opportunity now measures its comfort in actual degrees.

Bengaluru, the poster child of India’s tech revolution, is showing signs of burnout, and its Global Capability Centres (GCCs) are shifting the state’s economic geography in response.

The burnout that Bengaluru built

According to a TeamLease Digital survey published in The Hindu earlier this year, 83% of IT professionals in India report symptoms of burnout, with one in four clocking more than 70 hours a week. The stress peaks in Bengaluru, where two-hour commutes are routine and the line between work and life has all but disappeared.

In March, nearly 700 tech employees staged a march through Electronic City, calling for capped workweeks and mental health protections. A September UpToIndia report found that overwork, job insecurity, and poor managerial empathy account for 71% of burnout among tech workers, warning that up to 2.2 million professionals could quit the industry by year-end.

For Bengaluru’s GCCs—the global back offices of firms like Microsoft, Goldman Sachs and Honeywell—are feeling the strain, with attrition rates hovering around 18–22% and productivity showing signs of pressure. Traffic congestion and rising housing costs are no longer just lifestyle issues; they’re emerging as operational challenges for businesses.

The rise of Karnataka’s “Recharge Hubs”

That strain has sparked migration to the states’ known recharge hubs. From Mysuru’s leafy lanes to Mangaluru’s breezy coast, Karnataka’s Tier-2 cities are drawing in companies and talent alike, offering calm where the capital offers chaos.

According to a report on GCC location strategies (August 2025), setting up in these smaller cities cuts costs by 40–60%. But the real incentive is human. Shorter commutes, cheaper housing and a sense of community are proving stronger retention tools than any corporate perk.

The skill gap that once kept companies tethered to Bengaluru is narrowing fast. As noted in the state’s draft GCC policy, 60% of Karnataka’s AI and machine learning professionals now come from outside the capital. Retention rates are higher, too—evidence that rested employees think better, stay longer, and perform stronger.

At the centre of this shift is the Beyond Bengaluru initiative under the Karnataka Digital Economy Mission (KDEM). What began as a decentralisation policy has turned into a full-fledged wellness-driven growth model. According to a Deccan Herald report from September, the state plans to attract 500 new GCCs by 2029, generating 350,000 jobs and $50 billion in output.

Wellbeing is now built into policy. Companies get incentives for green-certified campuses, on-site counselling, and employee wellness programmes. Mysuru has emerged as a major beneficiary, with IBM and MiPhi Semiconductors setting up new facilities backed by ₹1,591 crore in EMC 2.0 funds. Mangaluru, meanwhile, is morphing into a coastal “Recharge Hub” anchored by the recently approved tech park—complete with ocean-view workspaces and wellness centres.

Between FY2021–22 and FY2025–26, KDEM-Zinnov data shows 47 new GCCs have entered Karnataka’s Tier-2 cities, with another 11 expanding operations. A Nasscom-Zinnov update this year found these centres now operate at up to 25% higher profitability—driven by lower costs and higher morale.

A new Centre of Gravity

This transformation hasn’t gone unnoticed. According to The Hindu, Telangana has pulled in 40% of India’s new GCCs over the past three years, powered by a ₹10,000 crore incentive policy. Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh are chasing similar targets. But Karnataka’s 2024–29 GCC policy gives it an edge—it was the first in India to tie wellness to economic incentives.

As part of that policy, the state now subsidises employee retreats through EPF contributions and is developing three new Innovation Districts, including one in Mysuru focused on green infrastructure. According to a Nasscom post from October, Karnataka could account for 55% of the country’s GCC growth by 2030. Inductus GCC’s August 2025 ranking already lists Mysuru and Mangaluru among India’s top eight Tier-2 contenders.

A state catching its breath

From Mazumdar-Shaw’s viral tweet to Shivakumar’s conciliatory meeting, the episode offered a small but telling glimpse of Karnataka’s current moment. Bengaluru’s infrastructure may be under strain, but the state’s ambition remains—it’s simply shifting to places that offer more room to grow.

For a state long defined by a single overworked metropolis, that shift marks a turning point. Karnataka’s emerging GCC landscape isn’t just about decentralisation—it’s about restoring balance and showing that even when the weather is good, people deserve better living and working conditions.